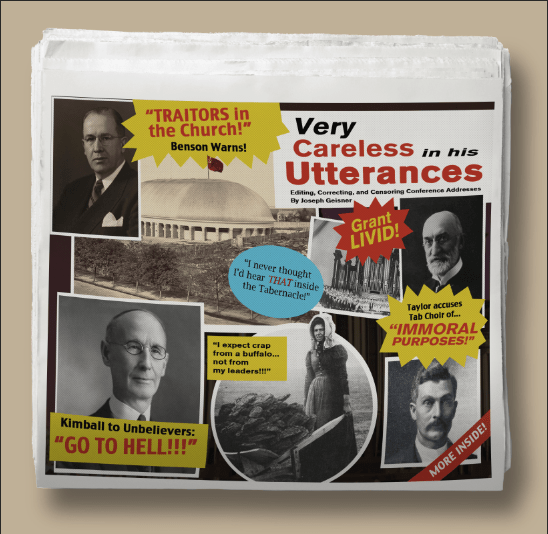

By Joseph Geisner

Or right-click to download the audio file here: “Very Careless in His Utterances”: Editing, Correcting, and Censoring Conference Addresses

At the Sunday morning session of the 3 October 2010 General Conference, President Boyd K. Packer gave a talk titled, “Cleansing the Inner Vessel.” However, the talk as published at LDS.org reflected changes to a few sentences and words.1 Almost instantly these amendments were being analyzed in the media and on the Internet. Some sources suggested that this kind of editing is actually common for general conference talks while others argued that the changes might mark a significant moment in Mormon history. One discussion board comment read:

A friend, who recently worked with the Church’s website, confirmed to me privately that ALL of the talks—not just some—were prepared in advance, run through Correlation and the FP’s office, and ultimately offered, word by word, during delivery. My friend said that nothing goes up on the website until all changes, even minuscule ones like adding, ‘My dear brothers and sisters’ at the beginning, are reconciled.2

On 8 October, LDS Church spokesman Scott Trotter released the following statement regarding the edits made in Elder Packer’s talk:

The Monday following every general conference, each speaker has the opportunity to make any edits necessary to clarify differences between what was written and what was delivered or to clarify the speaker’s intent.3 President Packer has simply clarified his intent.4

How often do speeches given in general conference undergo significant revision before publication? This article focuses on addresses given after the Church began publishing the Conference Reports, beginning with the October 1897 conference. My search found eleven speeches that had been either significantly edited before publication or altogether excised from the official published conference report.5

Two addresses delivered in the October 1898 General Conference did not appear in the corresponding Conference Report:6 “Morality and Chastity,” given by 40-year-old apostle John W. Taylor, a son of President John Taylor, and “Response to Elder Taylor,” by President George Q. Cannon, first counselor to President Lorenzo Snow. Both discourses were delivered 7 October 1898, and both were deleted from the official records of the conference and are not found in the Conference Report for that year. They do appear, though, in the fifth volume of Brian Stuy’s Collected Discourses.7

Taylor began his talk benignly enough but then startled the audience by reporting conversations with unnamed men who accused members of the Kamas, Utah Ward of having a conspicuous number of already-pregnant brides and accused members of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir of engaging in immoral practices.

Of the Kamas Ward, Taylor told conference attendees:

I was informed that eight out of every ten of the marriages there have been of such character that the wives have had children before they were married. Now, I can not believe that in Rhode’s Valley the Latter-day Saints are so rotten, as this man stated. I can not believe that they have so thoroughly rotted in the valley.

Then, of the Tabernacle Choir:

While conversing with this gentleman another man came up, whose word I could not doubt, and he said: “I was informed by a lady in Salt Lake who keeps a morning house, that after the close of practices by the Tabernacle choir, several members come to her rooming house for immoral purposes.”

After Taylor was finished, George Q. Cannon immediately stepped to the podium, chastised Taylor for his remarks, and tried to soothe the feelings of the accused. “We have regretted—I speak for the First Presidency—that there should be any mention of any particular place as being worse in this respect than others; for we have no reason to believe that this is the case.” Cannon said that if there were a problem it should be handled in a private, not public, setting.

Brigham Young, Jr., recorded in his diary that during the session, “Pres. Jos F. S[mith]. made some wise remarks followed by Bro Jno Taylor who made some very unwise remarks. Pres. Cannon stated Bro. T[aylor]. was wrong, had no right to speak on hearsay accusing innocent persons of immoral practices; laid some of it to his zeal. Pres. Geo. Q. C[annon]. was very kind to Jno. and allayed feeling which was aroused against Jno. W. T[aylor].”8

During the sustaining of the general authorities, held the Sunday after Taylor’s talk, “all were unanimous but in the case of John W. Taylor. Some few voted against him for remarks made on Friday about Kamas Ward and the Salt Lake Tabernacle Choir.” Following the Sunday solemn assembly, Elder Taylor “met with the choir and arranged his trouble with them.”9

According to George F. Richards, B.H. Roberts caused a stir on Wednesday, 6 October 1909, by spending almost an hour “for the most part devoted to a criticism of the present Church administration.”10 According to Reed Smoot’s account, Roberts “spoke of the faults and shortcomings of the Prophet Joseph and others and the necessity of keeping sacred an agreement &c. His whole remarks had behind them a spirit of fault finding but many of the things he said of and in themselves were fine. People wondered what he was driving at.”11 Apostle John Henry Smith commented that “Brigham H. Roberts made the longest talk of the conference, showing the mistakes of the saints during all time.”12 Apostle Orson F. Whitney admitted that Roberts was “eloquent,” but criticized the speech as “not imbued with the Spirit of the Lord. It caused sorrow to his friends, and doubtless gave aid and comfort to the enemy.”13

Roberts began by mentioning that he had been under the impression that he would not be addressing the conference but had been called on at the last minute. Indeed, Roberts had been at the center of controversy a few months earlier.

On 30 March 1908, Roberts had written a letter to Richard R. Lyman, a university professor, future apostle, and fellow Democrat, which subsequently “appeared in the daily papers” in early June 1908. The letter criticized Reed Smoot for running for re-election in the U.S. Senate while trying to simultaneously maintain an apostleship.14 In meetings with the Twelve and the First Council of Seventy during 5 and 6 January 1909, Roberts refused to apologize for the opinions he had expressed in his letter, declaring that those were “his views then, and that those are his views now.” Members of the two councils countered that “Roberts ought not to have written such [a]letter, [and that] he should have brought his grievance to this brethren.”15

Reflecting on Roberts’ talk and its roots, George F. Richards wrote that “the argument made by him before the Conference is, I judge, the argument he had prepared for his further hearing [about the earlier controversy] when it comes if at all.”

I could not find a transcript of Roberts’s original speech. But the language of the version published in the October 1909 Conference Report is still strong enough that it has caused me to speculate on how scathing the original talk must have been.

[T]ruth would compel me to say, as to events in the past, that our people have not always been blameless in their attitude as a community as to the things we have done. God has given us a system of truth that constitutes the Gospel of Jesus Christ—to my mind this Gospel is invulnerable; it is perfect, and unassailable with truth and reason. To defend it is a joy, and always a success. But our history—which is but another name for our conduct—is not always defensible at all points. While the Church in Missouri and Illinois never did anything that warranted the cruelty practiced upon them by the people of those states; and in the course of which there were violations of constitutions and the infringement of law—while all that was and is absolutely unjustifiable—yet there was much of fanaticism, much of narrowness, and bigotry, and un-wisdom on the part of individuals among the Latter-day Saints.

Doubtless everyone in the audience understood that President Joseph F. Smith’s harsh comments at the conclusion of the conference were aimed at Roberts. George F. Richards recorded that “Smith denounced [Roberts] and his talk in unmeasured terms without mentioning his name.” Orson F. Whitney believed that Smith’s “closing remarks were a dignified and telling rebuke to the foolish remarks made [by] some of the brethren.”16

Here is part of Smith’s reproof:

There never, perhaps, was a time in the Church when there were not foolish ones amongst us. Some have been foolish through overzeal; some have been still more foolish through lack of zeal, altogether,—some have been foolish in saying things they ought never to have said, and others have been guilty before the Lord in not saying that which they should have said. […] I think it is not wise or prudent for me to proclaim the short-comings of the Church if it has any, or the defects, faults, or failings of its members. I do not think it is my right or prerogative to point out the supposed defects of the Prophet Joseph Smith, or Brigham Young, or any other of the leaders of the Church. Let the Lord God Almighty judge them and speak for or against them as it may seem Him good—but not I; it is not for me, my brethren, to do this. Our enemies may have taken advantage of us, in times gone by, because of unwise things that may have been said. Some of us may now give to the world the same opportunity to speak evil against us, because of that which we say which should not be spoken at all.

George F. Richards wrote that he saw Roberts go “to the President when the benediction had been offered and just what was said I do not know i.e. what passed between them.” Richards then walked up and “shook the President’s hand and told him I thanked the Lord for those concluding remarks. I felt they were appropriate and needed.”17

On 15 October, about a week after conference had ended, Anthon Lund, second counselor in the First Presidency, recorded that “Roberts came in and told the President that if his speech was radically wrong he would let it be left out of the conference pamphlet. Prest. Smith said to him to submit it to me, and what I suggested would meet his mind. I told Bro. Roberts to make what changes he desired and we would go over it together.”18

Roberts’ edited address and Smith’s address are found in the October 1909 Conference Report (pages 101–108 and 123–125 respectively).

On 6 April 1915, apostle James E. Talmage delivered an address titled “The Son of Man.” On 10 May, five weeks after the conference, Talmage wrote in his journal that the conference report had “been delayed owing to a consultation regarding my own brief address.”

It seems Charles W. Penrose, second counselor in the First Presidency, was concerned that Talmage’s talk would “cause difficulty to the elders in the field, who he thinks would be confronted with the charge that we as a people worship a Man.” The parts removed included two paragraphs, a few sentences, and quotation marks. These omissions shed light on Penrose’s concerns. Talmage said that the title Son of Man “is applied to Christ to express His unique relationship to the human family, . . . [that] it was one of the highest titles that He could assume.” Talmage had also stated that “the Father of Jesus Christ, the Father of His spirit and the Father of His body, was a Man, and has progressed, not by any favor but by the right of conquest over sin, and over unrighteousness, to His present position of priesthood and power, of Godship and Godliness.”

In another paragraph, Talmage commented that if one saw “the Eternal Father sitting upon His throne, you would see a glorified, perfect Man.” This was changed in the published address to read that if one saw “the Eternal Father sitting upon His throne, one would see Him like a man in form.”

Although Talmage does not mention it in his journal, Penrose may have had a second concern with the talk. In Jesus the Christ, published the same year, Talmage writes that Jesus was the only male human being from Adam down who was not the son of a mortal man” (page 142). An omitted sentence in the conference address reads: “Jesus Christ was the only male human being that has ever walked the earth since Adam who was not the son of a mortal man.” It appears that Talmage was saying in Jesus the Christ that Jesus was the only human born of a divine father; but in the talk, he leaves a loophole for Adam to also be the son of a divine father.19

Talmage included the complete, unedited version of his conference address in his journal; it was reprinted in The Essential James E. Talmage published by Signature Books in 1997. “President Joseph F. Smith desired that the full and original report be preserved,” Talmage wrote in his journal. His theology is found in chapter two of Jesus the Christ under the subheading, “The Son of Man,” pages 142–144.

On 7 October 1923, J. Golden Kimball, a member of the First Council of Seventy, gave a “brief speech” that caused President Heber J. Grant to leap to his feet. According to the Ogden Standard Examiner, Kimball

told of having last year received a Christmas present C.O.D. Then he pointed the moral. “Of course I paid for it,” he said. “That’s the way God’s blessings come—C.O.D. You don’t get anything unless you deserve and pay for it.” The genuine sensation came when Mr. Kimball bearing testimony to the truth of Mormon faith said, “I know that the Mormon gospel is true, that Joseph Smith was a prophet of God, and when I know a thing I know it. Why worry about what the other fellow says. As far as I am concerned they can go to hell and that’s where most of them belong.” Mr. Kimball took his seat without the usual “in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.” President Grant at once arose and said, “Pardon me, but I do not desire that laughter be provoked in our worship.”20

The Salt Lake Telegram, reported that Kimball’s “last statement brought laughter from the large crowd, and President Grant, evidently provoked at the proceedings, arose and said: ‘Pardon me, but I do not desire that laughter be provoked in our worship.’”21

The Deseret News blandly reported: “Elder Kimball testified he knew God lived and that he expected pay for all blessings and promises given.”22

On 9 April 1932, apostle Stephen L Richards gave a conference address titled “Bringing Humanity to the Gospel,” which the Salt Lake Tribune described as “the keynote message” on the second day of conference.

Richards expressed concern about members of the Church who looked down upon fellow Mormons who used tobacco, tea, or coffee, or those who played billiards or games involving face cards. Near the end of Richards’ talk, he said poetically:

I have said these things because I fear dictatorial dogmatism, rigidity of procedure and intolerance even more than I fear cigarettes, cards, and other devices the adversary may use to nullify faith and kill religion. Fanaticism and bigotry have been the deadly enemies of true religion in the long past. They have made it forbidding, shut it up in cold grey walls of monastery and nunnery, out of the sunlight and fragrance of the growing world. They have garbed it in black and then in white, when in truth it is neither black nor white, any more than life is black or white, for religion is life abundant, glowing life, with all its shades, colors and hues, as the children of men reflect in the patterns of their lives the radiance of the Holy Spirit in varying degrees.23

Immediately after the session, according to Talmage’s journal, the First Presidency and the Twelve met to discuss whether to allow the talk “to be published in full at this time.”

Brother Richards urged a tolerant and kindly attitude toward those of our people, particularly young people, who become addicted to some habits in violation of the revelation known as the “Word of Wisdom,” and a question has been raised as to whether the effect of this address will be that of leading to the thought that the Church is lowering its standards.24

Two days later on 11 April, Church president Heber J. Grant recorded in his diary that mission presidents and stake presidents “were disturbed about Brother Stephen L. Richards’ talk.”25 On two different days, 22 April and 2 May, Richards wrote a letter to two different friends expressing the hope that his discourse “will be helpful to better understandings, and that no one will get from it the impression that I desire to lower the high standards to which we have always held.” On 26 April, apostle David O. McKay noted in his diary that he, Richards, and Joseph Fielding Smith were busy editing Richards’s talk.

During a 5 May meeting of the First Presidency and the Twelve, Richards refused to change his talk for publication and even offered to resign his apostleship. After the meeting, Grant told McKay and Anthony Ivins that Richards had “made a mistake when he delivered that address, but today he made a fool of himself.”26 That evening, Grant confided in his diary “that it would be a mistake to publish” Richards’s address.27

During an 8 May visit from Grant in Washington D.C., apostle Reed Smoot recorded in his diary that “[Grant] told me of the unfortunate remarks Stephen L. Richards made at the last conference. Stephen L. was ready to resign but Pres. Grant thought that would not happen.”28

Indeed, Richards told Grant on 26 May “that he [Richards] felt he had made a mistake by preaching [his address] and it was all right with him [for the First Presidency to take] whatever action [they] saw fit . . . regarding it.” Grant recorded that he was “very happy to have [Richards] make this confession,” because he had a “great deal” of worry during the trip east.

On 27 May, Grant told a staff member of the Improvement Era that the magazine could not publish Richards’s talk.29 On 30 May, Grant wrote to Smoot saying that it would have been very difficult to print Richards’s address since the text would need to be accompanied by a statement, which would call more attention to the talk. Grant decided to “let the matter drop, and if it doesn’t appear in the Conference Pamphlet it will soon be forgotten that the speech was made.”30

The address was not published until Sunstone magazine printed it in 1979. However, the talk Sunstone published is not the original talk delivered at the conference.31

In the original draft of the talk, which has never been published, Richards wrote, “Some important changes in the ordinances, forms and methods have been made in recent years.” Both the endowment ceremony and the temple garment had undergone major changes in the ten years prior to this address, and the topic was still a sensitive one.32 So, in other unpublished edited versions, “in the ordinances, forms and methods” was removed. In its coverage of general conference, the Salt Lake Tribune reported Richards as saying, “I hold it entirely compatible with the genius of the Church to change its forms of procedure, customs and ordinances in accordance with our own knowledge and experience. I would not discard an old practice merely because it is old, but only after it has outworn its usefulness.”33 If this report is accurate, then Richards may have been advocating changes in the ordinances of the Church.

Also removed from an edited version was Richards’ advice that the Church should work with members who did not follow the Word of Wisdom or the Church’s injunctions against billiards and face cards: “I would modify the campaign and the counsel and surround them with safeguards which I think have often been lacking,” he said. The edited version reads, “But I would surround the campaign and the counsel with safeguards which I think have often been lacking.”

Despite—or perhaps because of—the disturbance this talk created, Richards became David O. McKay’s first counselor in 1951.

J. Golden Kimball was again rebuked when he addressed General Conference on 9 April 1933. On 10 April 1933, the Deseret News briefly summarized Kimball’s speech under the subtitle “Prejudice Scored.” The report read, “Elder J. Golden Kimball, one of the Seven Presidents of the Seventies, in a short address cautioned against prejudice, claiming that ‘no man on earth can be prejudiced and still be just.’” The 10 April 1933 Salt Lake Tribune, provided an equally succinct account: “Mr. Kimball urged members of the church to avoid prejudice, declaring that no man can be prejudiced and be just. He said it is particularly important that parents do not adopt a prejudiced attitude toward their children.” However, according to Heber J. Grant, Kimball had told the audience, “God, how I hate prejudice” and “that he loved some of them a damn sight better than others.” Grant apparently used part of his own speech to take Kimball to task for his off-color language.

On 16 April 1933, Heber J. Grant recorded that Edward P. Kimball, Golden’s nephew and the Tabernacle organist, confided that his uncle’s language during the conference session had humiliated him and that he was very glad that Grant had rebuked “Uncle Golden.” Three weeks later, on 5 May, Grant went to Golden’s office to discuss the talk; Golden was absent, but two of Golden’s half brothers, Joseph and Albert, were present and pointed out that Grant’s own published speech would make no sense if Golden’s were revised.34

On 19 May 1933, Grant finally met with Golden to discuss the talk. Here is the account from Grant’s diary:

I told him that under no circumstances would I consent to having his speech remodeled the way he had changed it, because it would be a direct reflection on anything I said, because there would be nothing there to criticize. I told him plainly that he must quit using the name of God, that I considered it absolute profanity when he said “God, how I hate prejudice,” and when he referred to his conversation with Brother Lyman, in which he told Brother Lyman, in answer to his question as to whether he loved the brethren, that he loved some of them a damn sight better than others, that it was absolutely ridiculous to talk that way. I told him I wanted him to understand that I wouldn’t and could not sustain him as one of the General Authorities of the church if he did not change. He said he would do his best to improve. He further said that if I did not want to publish his remarks it would be all right with him. I said, “I am going to publish your talk in full and mine, too, unless you want me not to.” He said he would prefer not to have his talk published. I tore it up and threw it into the waste-basket. I was disappointed over my interview with him, from the fact that he did not come out frankly and fully and say “Brother Grant, I apologize; I did wrong and I am sorry.” But we are all differently constituted, and I was glad to have a talk with him and to have him assure me he would endeavor to mend his ways. I read my talk to him word for word as it was delivered, in which I referred to my love of him, his testimony of the Gospel, etc., and there is practically no criticism whatever in it. I told him that if I had referred to his taking the name of God in vain and insulting his senior president, etc., there might have been some complaint, but I made it as mild as I know how. Golden is given to being very careless in his utterances, and I do hope and pray that he will change in the future. I always have liked him. He is fearless and has a strong testimony of the Gospel, but he is as careless in his talk as mortal man can be. He pledged his absolute loyalty to me, but I would think more of his pledge if he would be more careful in his talk.35

Kimball’s talk does not appear in the April 1933 Conference Report, nor does the published report contain any reference to his talk. Apparently Grant’s talk was completely reworked before the Conference Report was published to remove references to Kimball.36

Though this is only speculation on my part, it seems to me that Kimball’s remarks at the conference were extemporaneous. The talk that Grant tore up may therefore have been the one created by the conference recorder, making that document the only record of the talk.

Continued in Part II

Comments are closed.